By Linda Austin

Konnichi wa, obaasan, o-genki desu ka?

My Japanese mother suffered from Alzheimer’s. She spent her last three years in a care home and I went there nearly every day to spend time with her and to help care for her. She had forgotten most of her Japanese but her eyes would light up when I greeted her with my rudimentary Nihongo language skills, marveling how I had found her there and how this very American daughter knew some Japanese words. Thank goodness she always knew who I was.

I made a lot of new friends at the care home, dear elderly men and women, many of whom had degrees of dementia. My mother’s mother, the Japanese grandmother I had never met, apparently also had some kind of dementia in her last years, so I worried that I, too, would get Alzheimer’s disease, which was why I had started trying to learn Japanese. I wanted to exercise my brain. After my mother was moved to the dementia care wing, since I was spending so much time there I decided to challenge my brain even more by writing poetry.

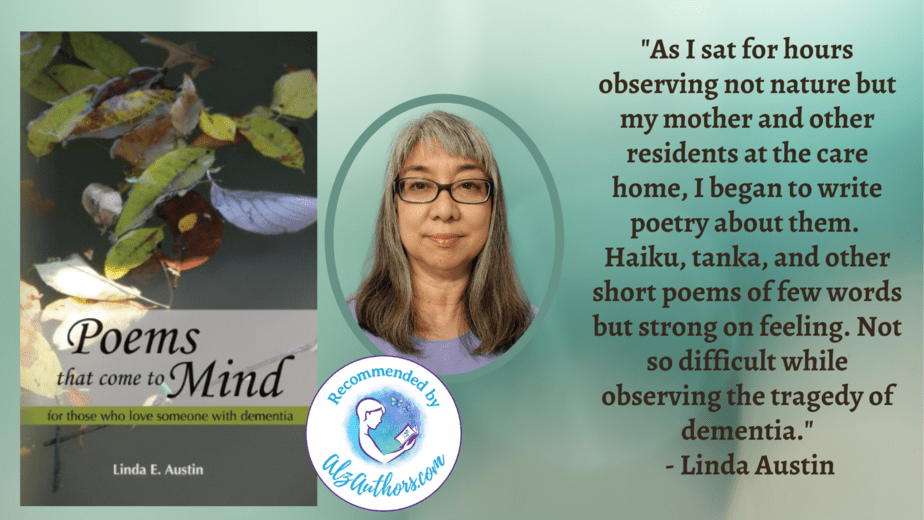

My mother had recalled, while I was writing her youthful stories of living in Japan around WWII, that one of her grade school teachers had taken the class to nearby woods where she told them to “listen carefully.” She said that to write haiku we needed to “get close to nature, to hear or see things, and then find the feelings inside ourselves.” And so as I sat for hours observing not nature but my mother and other residents at the care home, I began to write poetry about them. Haiku, tanka, and other short poems of few words but strong on feeling. Not so difficult while observing the tragedy of dementia.

My mother had recalled, while I was writing her youthful stories of living in Japan around WWII, that one of her grade school teachers had taken the class to nearby woods where she told them to “listen carefully.” She said that to write haiku we needed to “get close to nature, to hear or see things, and then find the feelings inside ourselves.” And so as I sat for hours observing not nature but my mother and other residents at the care home, I began to write poetry about them. Haiku, tanka, and other short poems of few words but strong on feeling. Not so difficult while observing the tragedy of dementia.

The most eloquent poetry comes from deep emotions, and I felt deep pain as well as a deep love I had never had before with my mother. We had always had an up-down relationship that only later in life I discovered was mostly due to cultural differences and her experiences of poverty and war that I did not understand or have patience with. But in her deepening dementia, she needed me and appreciated my presence and care, and the barriers came down.

I loved spending time with my mother and the other residents and found many sweet, quiet moments with them, even amusing ones in the midst of the pain. These moments found their way into poems, and eventually I had enough to make a little booklet that I thought would speak to others who were caregivers for loved ones. It’s called Poems That Come to Mind: For those who love someone with dementia. Our first Missouri Poet Laureate, Walter Bargen, whose mother was suffering from Alzheimer’s, said, “Each delicately and fiercely imaged poem is a tribute to perseverance and survival and a lesson for us all.” Shortly after the book was published, my mother ever so slowly and gently passed away to freedom.

On the Alzheimer’s/dementia journey, we who care for our beloveds are ourselves often left without words. Without words to express what we feel watching someone we love be confused, fearful, even angry, and yet needing us so badly, like a child, to be there for them with patience, understanding, and unconditional love. In the tragedy, we have to be reminded of the shining, precious little moments of sweetness that do exist. Laugh, love, and treasure those moments.

We sit side by side

Holding hands in the soft sun

Soon we fade away

Dozing in warm nothingness

Lost in the dove’s lamenting

Purchase Poems That Come to Mind: For those who love someone with dementia on Amazon

About the Author

Linda Austin is the author of Poems That Come to Mind: For Those Who Love Someone with Dementia and her mother’s WWII memoir, Cherry Blossoms in Twilight, which Linda used to remind her mother of childhood stories and songs. Linda is an advocate for life writing through her Moonbridgebooks website and blog and Facebook Page Moonbridge Life Writing and Memoir. Find her on Twitter at @moonbridgebooks and on Instagram at moonbridgebooks.

Linda Austin is the author of Poems That Come to Mind: For Those Who Love Someone with Dementia and her mother’s WWII memoir, Cherry Blossoms in Twilight, which Linda used to remind her mother of childhood stories and songs. Linda is an advocate for life writing through her Moonbridgebooks website and blog and Facebook Page Moonbridge Life Writing and Memoir. Find her on Twitter at @moonbridgebooks and on Instagram at moonbridgebooks.

Connect with Linda Austin

One Response

What a tender and moving piece. Thank you for sharing the up’s and down’s we experience with our loved ones, and ultimately the inevitable surrender.