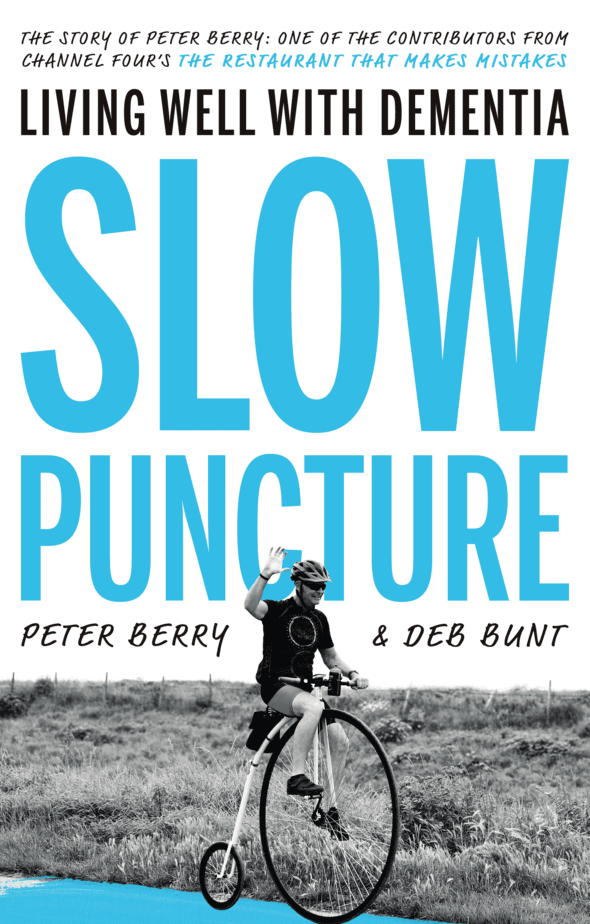

AlzAuthors contributor Deb Bunt, author of Slow Puncture: Living Well With Dementia, guest blogs for us in honor of World Alzheimer’s Month. Deb believes it’s essential that those living with dementia tell their stories while they can, and she offers suggestions on how to get this done. Here she tells her story of working with her friend Peter Berry to help him tell his Alzheimer’s story. Next week, on September 23rd, she reports on her interview with Wendy Mitchell and how she tells her story via her blog, Which Me Am I Today?, and her book, Somebody I Used to Know, written with the help of Anna Wharton. Lastly, coming September 30th, she shares her discussion with Dr. Jennifer Bute, whose story is told in Dementia From the Inside, written with Louise Morse, and on her blog, Glorious Opportunity.

By Deb Bunt

My friend, Peter Berry, is one of the most talkative, engaging, and imaginative people I know. Peter can capture an emotion, an event, a situation effortlessly and he uses metaphors flamboyantly as if he had studied the art of writing for years.

My friend, Peter Berry, forgets what he has said, what emotions he has felt, where he has been, and the magical power behind his words. Peter wouldn’t necessarily know a metaphor if it leapt out in front of him and performed two double somersaults before taking a theatrical bow.

My friend, Peter Berry, forgets what he has said, what emotions he has felt, where he has been, and the magical power behind his words. Peter wouldn’t necessarily know a metaphor if it leapt out in front of him and performed two double somersaults before taking a theatrical bow.

Often, those who meet Peter and hear him talk do not believe that he is living with early onset dementia. They are incredulous that he can’t remember what he has said, so skilled is he at being the showman. I found it hard to believe this at first too.

From day one, when I met Peter, the conversation flowed, and his anecdotes amused me. Peter is like Othello who claimed to be “rude…in speech” but quite clearly had mastered the art of hyperbole, metaphor, and oration. Peter gives the impression that he was born to talk. And quite possibly he was. And most definitely he still can.

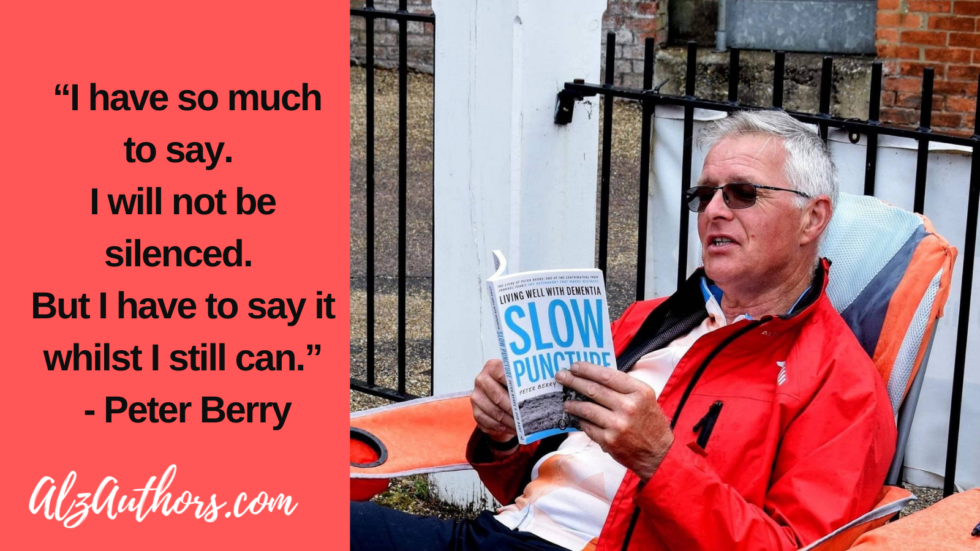

But something moved me and stuck in my mind as my friendship with Peter grew. Once, over coffee break during one of our cycle rides, he said, “I have so much to say. I will not be silenced. But I have to say it whilst I still can.” That last sentence now sends a chill through me.

As soon as Peter has handed over his words, his stories, his emotions to me they are gone from his mind. They tumble from his mouth, and I scamper around and catch them in my word-catcher butterfly net. I pin these precious gifts down, label them, store them carefully and display them for others to admire when the moment is right.

Recently, when struggling to remember if he had told me an incident which had happened that morning, Peter said, “When I hit enter, the information disappears; you are my plug in and save device.”

And I feel a myriad of emotions at this statement: I am happy and touched that I am his “plug in and save device” (after all, I have been called worse things in my life); I am sad and angry with dementia for making it necessary that I assume this role; I am moved by the words and clutch them to me, with a quiet desperation; and yet I am full of fear for the day when Peter’s words will dry up.

As Peter’s scribe, my job is to protect his words and his life from dementia’s ruthless march forward. This is how our book, Slow Puncture, was conceived and this is how our next project, Peter’s poetry, is evolving too.

As Peter’s scribe, my job is to protect his words and his life from dementia’s ruthless march forward. This is how our book, Slow Puncture, was conceived and this is how our next project, Peter’s poetry, is evolving too.

I have known Peter for three years now and I can see the value I provide to both him and his wife in recording his words and his days. Despite the inevitable repetition, I love to listen to Peter’s stories. Depending on my own mood, I hear different things from the same story. That’s a lesson to us all: never tire of listening to someone’s past, it can teach us so much. These narratives are wonderful gifts and should be treated as such.

Peter and I are from totally different worlds and backgrounds: I was born in London where I lived for many years. I have travelled across Europe and Asia; I have lived in Vienna and New York. In truth, I am a restless itinerant who has only recently found a firm foothold in the glorious Suffolk countryside. Peter was born in a small Suffolk town and, at sixteen, worked at and then managed the family’s timber trade across the Suffolk coastal area. For the past twenty-five years he has lived in a village, barely ten miles from his hometown.

Yet his stories encapsulate all human life. Without Peter and his yarns, without the splendid array of colourful characters who march joyously into his stories and whom he recalls with such fondness and relates with such humour, my life in Suffolk would be significantly duller. His anecdotes both educate and enlighten me.

The importance of being Peter’s “plug in and save device” cannot be underestimated. Perhaps Peter cannot remember what he had for lunch, but this does not mean his stories and his past must also be forgotten. I am reminded of a conundrum my father used to tease me with: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” Peter’s words are like that tree; they must be heard and be captured for him, for his family and for other people.

Peter once said, in a typical throwaway line, that he wanted his voice to be played on a gramophone for all to hear.

“Your job,” he said “is to be the stylus. I might have the messages to share, but people will hear nothing without a stylus.”

He’s right, of course. If I did not listen to Peter, if I did not fulfil my role as a stylus, then Peter’s stories would remain inaudible at best or, worse still, remain untold. Both the gramophone and the stylus must work in synchronicity. Between us we can blast Peter’s words at full volume to those who want to listen. Because what we are playing are memories, emotions, fears, and joys. Dementia should not be a bar to the ability to share all of these with those who want to listen. If you get the opportunity to be someone’s stylus, or scribe, start taking notes. It’s worth it.

Purchase Slow Puncture: Living Well With Dementia on Amazon.

About the Author

About the Author

Deb Bunt is married with two sons and two grandchildren. She’s retired from working as a family practitioner and living in glorious Suffolk, where her days are spent with friends and family, cycling, drinking coffee, eating cake, trying to play Beethoven on the piano and, above all, trying to perfect the skill of “living in the moment.”

Connect with Deb and Peter