A few days before my sixty-first birthday, I was diagnosed with cerebral microvascular disease, which is the leading cause of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease. My mother also had dementia.

My diagnosis was not a total surprise—for about five years I had a short-term memory loss that led to pots on the stove at home boiling dry, washing my hair twice in an hour, forgetting to bake a casserole I had made the night before. At work, it led to a slowness in my job as the associate director of the Gender Studies Program at the University of Utah, trouble remembering what I had prepared for class while teaching, embarrassments such as asking people in a meeting to introduce themselves when they had already done so.

Given my suspicions, my diagnosis came as a relief: I was not just being lax or not trying hard enough, or imagining things. The white spots on my MRI and 20-point drop in my IQ were very real. The diagnosis was also a wake-up call: how was I going to live with joy and engagement during the 15 years I probably had left? How was my family—husband Peter and children Marissa and Newton and their spouses—going to live with and care for me?

From the time my children were small, our family had talked about what each of us thought of as a worthwhile quality of life and how to consciously live during each of its stages. Questions arose: What does a worthwhile life look like for someone with dementia? What will be the markers for when my life no longer has the kind of quality I value? Will my family be prepared to support the legal assisted death I wish for when my life no longer meets my criteria for a meaningful life? Our family talked about end-of-life issues and how each one of us interpreted a worthwhile life. In my book I list some of my criteria for a worthwhile life and share how my children and their spouses have given me their support in my quest for a legal self-death, and how we formalized our arrangements with my doctors and a lawyer.

Completing my end-of-life plans was enormously comforting. I could get on with my life. I could participate in family activities, figure out how to get around after I gave up my driver’s license, enjoy reading (which includes a lot of re-reading, because I forget), working in my garden (many bruises attest to my lack of balance)—in other words, live joyfully each day. Might I even be able to fulfill my retirement goal of writing a book?

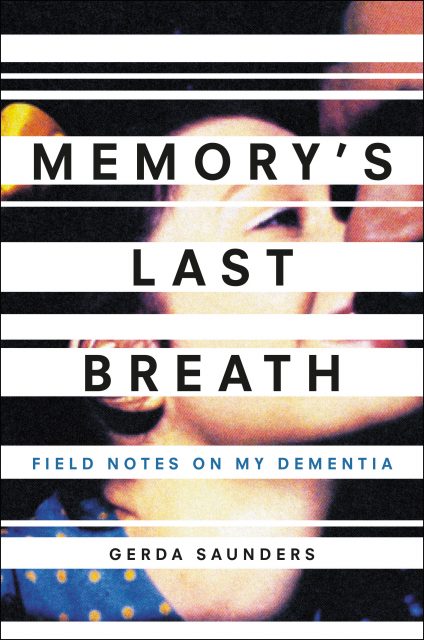

When I retired after my diagnosis, I started a journal to document my daily difficulties. With a wink at my bachelor’s in science, I called it Dementia Field Notes. I would be an anthropologist, following the life of one member of the tribe of Dementers—myself. My journal entries led to essays that tackled the questions: What, actually, is memory, personality, identity? What is a self? Will I still have a self when my reason is gone? How come I can’t make coffee without mishaps, but can still write? My essays became the chapters of Memory’s Last Breath.

The purpose of my book is this: to add my personal story to the vast body of science about dementia accumulated by the lifetime efforts of neuroscientists, neuropsychologists, other medical researchers, and healthcare providers.

My book is for you, whether you pick it up because you or someone you love has dementia, or because you’re a medical professional, or a person searching for your own self after a huge life change, or someone just plain curious, who—like me—feels that the more you know, the better you love.

About the Author

GERDA SAUNDERS grew up in South Africa, where she obtained a B.S. in Math and Chemistry from the University of Pretoria. After working as a research scientist at the South African Atomic Energy Board for three years, she taught Science and Math at Kempton Park (Afrikaans) High school and Math and Physics at the Kempton Park Technical Institute. In 1984, she settled in Utah with her husband Peter and two children. While enrolled in an English PhD at the University of Utah in 1996, she taught Business- and Creative Writing. After graduation, she worked for seven years in the business world as a technical writer and program manager. In 2001, she became the Associate Director of Gender Studies at the University of Utah. In addition to her administrative role, she taught classes in gender studies and English Literature. In 2002, SMU Press published her stories Blessings on the Sheep Dog, about which Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee said, “With cool intelligence, laconic wit, and deep feeling, Saunders explores the moral chaos of South Africa and the pain of a new generation of…exiles.” At the time of her sixty-first birthday, she received a diagnosis of microvascular disease, a precursor of dementia. Having retired shortly after her diagnosis, she now enjoys time with her family, including three grandchildren. Other interests are community work and writing. In Winter 2013, The Georgia Review published her essay about the effect of her brain’s unraveling on her identity, “Telling Who I Am Before I Forget: My Dementia.” The essay was reprinted in other publications, including in the online magazine Slate. From Saunders’s essay grew a memoir, Memory’s Last Breath: Field Notes on My Dementia (2017).

GERDA SAUNDERS grew up in South Africa, where she obtained a B.S. in Math and Chemistry from the University of Pretoria. After working as a research scientist at the South African Atomic Energy Board for three years, she taught Science and Math at Kempton Park (Afrikaans) High school and Math and Physics at the Kempton Park Technical Institute. In 1984, she settled in Utah with her husband Peter and two children. While enrolled in an English PhD at the University of Utah in 1996, she taught Business- and Creative Writing. After graduation, she worked for seven years in the business world as a technical writer and program manager. In 2001, she became the Associate Director of Gender Studies at the University of Utah. In addition to her administrative role, she taught classes in gender studies and English Literature. In 2002, SMU Press published her stories Blessings on the Sheep Dog, about which Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee said, “With cool intelligence, laconic wit, and deep feeling, Saunders explores the moral chaos of South Africa and the pain of a new generation of…exiles.” At the time of her sixty-first birthday, she received a diagnosis of microvascular disease, a precursor of dementia. Having retired shortly after her diagnosis, she now enjoys time with her family, including three grandchildren. Other interests are community work and writing. In Winter 2013, The Georgia Review published her essay about the effect of her brain’s unraveling on her identity, “Telling Who I Am Before I Forget: My Dementia.” The essay was reprinted in other publications, including in the online magazine Slate. From Saunders’s essay grew a memoir, Memory’s Last Breath: Field Notes on My Dementia (2017).

Amazon: Memory’s Last Breath

Gerda’s website

Gerda on Facebook

Gerda on LinkedIn

Gerda on Twitter

Gerda on Pinterest

3 Responses

Thank you for sharing your story.

I love how you and your family haven’t shied away from the difficult issues inherent with your disease. Congratulations on putting sentiments into words from which all of us can benefit.

I loved ‘true’ stories. They tell it like it really is. Thank you Gerda Saunders, you open our eyes with your words.