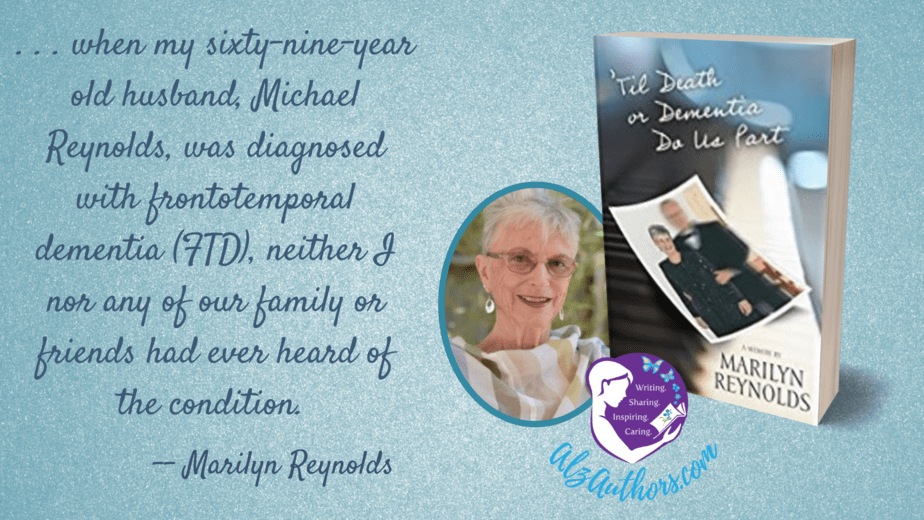

By Marilyn Reynolds

In July of 2009, when my sixty-nine-year old husband, Michael Reynolds, was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), neither I nor any of our family or friends had ever heard of the condition. Upon delivering the diagnosis, the neurologist explained that FTD is a neurodegenerative disease that affects the frontal and temporal regions of the brain–regions that control personality and social behavior, reasoning, speech and language comprehension, and executive functions. There is no known cause. No cure. It is progressive, but the rate of progression is unpredictable. Aricept and/or Namenda, drugs often used to slow the onslaught of Alzheimer’s, might in some cases slow the progression of FTD, though that, too, is uncertain.

We were all certainly aware of Alzheimer’s. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that 60 to 80 percent of all cases of dementia result from Alzheimer’s disease. Vascular dementia, caused by inadequate blood flow to the brain such as often occurs with strokes, accounts for 20 to 30 percent, FTD perhaps 10 to 15 percent. I, our grown children, my brother and sister-in-law, and some in our close circle of friends set about gathering and sharing whatever information we could find. In comparison to the wealth of Alzheimer’s publications and media reports widely available, information about FTD was scarce and required a degree of diligence to uncover. (Thankfully, much has changed since 2009 and FTD related information is much more readily available). I hungered for stories of everyday caregivers dealing with loved ones with FTD, but could find none. Of course, there is much overlap of caregiving experiences with any dementia, but there is also much that is unique to FTD.

While those of us who loved Mike familiarized ourselves with whatever information was available, we watched as he increasingly displayed the classic FTD symptoms the diagnosing neurosurgeon had enumerated. He lost his ability to reason or to be reasoned with, his capacity for empathy, and all aspects of his previous good judgment.

As I struggled to care for Mike, learning mostly by trial and error what might work and what wouldn’t, figuring out where and how to seek help, all while dealing with a tremendous sense of loss and grief, I vowed to write the book I had wished to read after receiving that 2009 diagnosis, the true story of an everyday caregiver’s experiences and insights. A story that might help others in similar situations feel less alone.

Mike was a professional musician, a singer, choral director, and teacher. He had a wide circle of friends, people who cared about him and wanted to know what was happening to their previously dependable, caring and connected friend. I tried to keep people informed, emailing after every doctor’s visit or new development. I later came to realize that my hit and miss email style left some in the dark who wanted to be included, and likely included some who would just as soon not to know the details. I decided to keep a blog. People could follow or not according to their own preferences. The blog ultimately offered the foundation of details and events that enabled me to write our story.

As for assisting those living with a loved one with dementia, ‘Til Death or Dementia Do Us Part offers a short “Just the Facts” timeline of behavioral changes and medications used; a short section of “Where to Find Help,” and insights and experiences to consider “For the Sake of Your Own Sanity.” In my opinion, though, the greatest value to one living with a loved one with dementia is the personal story with which caregivers can connect and, perhaps, feel less alone.

About the Author

Marilyn Reynolds is the author of eleven books of realistic teen fiction in the “True-to-Life Series from Hamilton High;” a book for teachers, I Won’t Read and You Can’t Make Me: Reaching Reluctant Teen Readers; a collection of essays, Over 70 and I Don’t Mean MPH: Reflections on the Gift of Longevity; and ’Til Death or Dementia Do Us Part, the chronicle of her life as a caregiver for her husband as he sank into the prison of frontotemporal dementia. She is currently at work on Over 80 and I Don’t Mean MPH.

Marilyn counts herself fortunate to be the mother of three grown children and the grandmother of five. She lives in Sacramento, California, where she enjoys walks in her East Sacramento neighborhood and along the levee of the American River. In non-Covid times she enjoys dinners and movies out with friends and family

Connect with Marilyn:

Website: www.marilynreynolds.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/marilyn.reynolds1

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MReynoldsauthor