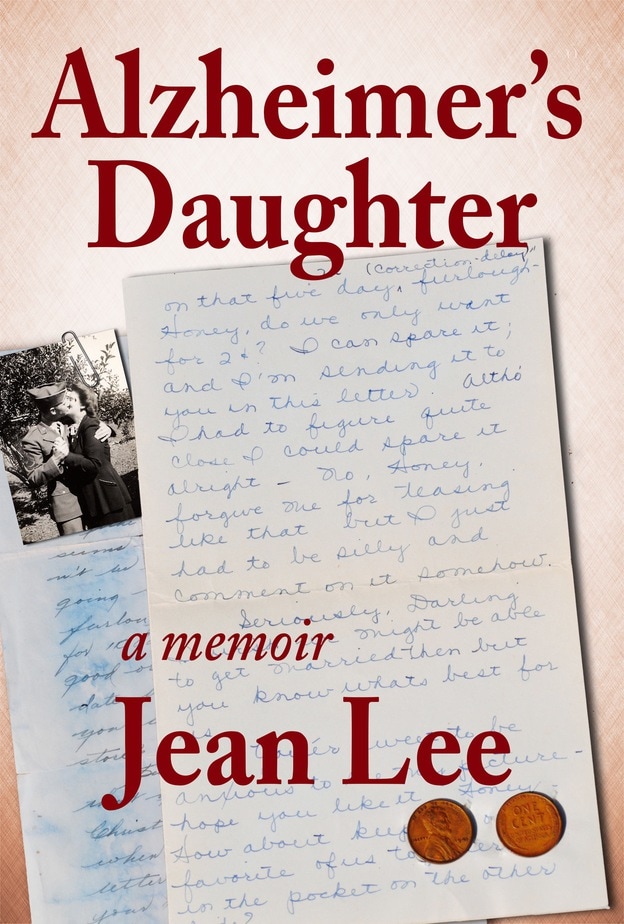

Alzheimer’s Daughter by Jean Lee

Alzheimer’s Daughter by Jean Lee

Blue Hydrangeas by Marianne Sciucco

Blue Hydrangeas by Marianne Sciucco

What Flowers Remember by Shannon Wiersbitzky

What Flowers Remember by Shannon Wiersbitzky

Somebody Stole My Iron by Vicki Tapia

Somebody Stole My Iron by Vicki Tapia

Alzheimer’s Daughter

By Jean Lee

My mom and dad were both diagnosed with Alzheimer’s on the same day. Mom declined for eight years and Dad for nine, until they died. Our journey became my memoir, Alzheimer’s Daughter, the story of preserving their dignity while weighing difficult options to ensure their safety.

Although my parents did not live with me, I lived one mile from them in rural Ohio and became their primary caregiver and decision-maker.

My only sibling, a sister, lived 1,000 miles away in Florida. Reading those words, you might expect conflict, but there was none. My sister and I grew a deeper relationship during our parents’ illness. She was my total support, my therapist by phone. She was willing to take on the tough role of ‘bad cop’ so I could remain the loving caregiver.

Prior to the diagnosis, we observed our parents’ progressive mental regression for about three years. When I talked with my sister by phone, I’d mention my concerns. She encouraged me to begin a journal of oddities. I hid the notebook in the bottom of my kitchen junk drawer, regarding it as tattling—the writings of a traitor.

While my parents were ill, I was a third grade teacher, loving my job, and the children I taught. My job became my refuge, my normalcy.

I confided with only a handful of colleagues. They were astonished by the dual decline of both parents and told me I should write a book. I struggled to stay afloat and barely had time to write lesson plans. Their comments went in one ear and out the other.

Until…

A conversation with my father one week after my mom died changed everything. I was stunned to realize he had no memory of the woman he adored, or their 66-year marriage. At that point I became a writer. I knew this story had to be told.

I fleshed out the chicken scratched, sister-journal to include my feelings as we sought a diagnosis, moved our parents out of their life-long home and suffered the guilt of stripping everything from the ones who had provided us everything.

The journal formed the middle part of Alzheimer’s Daughter, bookended by a beginning chapter about our parents’ relationship and the way they raised us, ending with a series of three moves, eventually to a locked memory care unit where they died with my sister and I holding their hands.

Added to the story as chapter beginnings are Mom and Dad’s WWII love letters, which I found as I cleaned out their house. These letters contrast their love and devotion—their vows for better or worse, in sickness and health—with their inability to care for each other as the disease shattered them both.

In my opinion, these letters are the most beautiful part of the book.

The book concludes with my letter to them.

I hope Alzheimer’s Daughter honors my parents, their positive attitude, and their love story.

I spent three years writing the book and a year agonizing about whether it should remain a private, family story, or become public. While pushing the final “publish” button, I thought I might be struck by lightning as punishment for revealing something so intimate. Now a year later, people I’ve never met have helped me heal by telling me through reviews that the story has helped them cope.

###

Blue Hydrangeas

By Marianne Sciucco

From my early days as a nurse I’ve had a soft spot for dementia patients. Most people are unfamiliar with the day to day pain and loss this disease brings. Blue Hydrangeas, an Alzheimer’s love story is my attempt to tell the heartbreaking story of dementia, and to honor the more than 5 million living with Alzheimer’s and the people who love and care for them.

One day at work as a nurse case manager in a rehabilitation unit, I met an elderly couple who inspired my characters Jack and Sara. She had Alzheimer’s, and he was physically frail. The amazing thing about them was that they’d driven from Florida to New York by themselves without any incident. Unfortunately, once home she fell and broke her pelvis and landed in the hospital. That’s where I came in, to assist with the discharge plan. She was supposed to go to a local nursing home for continued rehab and her son planned to drive her and her husband there on discharge day. I completed their plans and said goodbye, but couldn’t stop thinking about them, wondering what would happen if they somehow left the hospital without their son and did not go to the rehab. Where would they go? What would they do? My wild imagination took off, and the seeds for the novel took root.

The response from readers is both satisfying and humbling. When I published I had no idea if the book would find an audience, but within weeks I’d received several 5-star reviews from caregivers who thanked me for writing “their” story. A later reviewer called it “healing,” and another said it was “grief release.” A favorite comment is “Read it twice just to make sure I didn’t miss anything.” I could not have hoped for a better response.

As a nurse, I’m proud to help others dealing with this disease. As an author, I’m grateful this important topic found me, and that I had the determination and fortitude to bring this book to completion.

Knowing that I have not only touched lives but validated the experiences of these unsung heroes is one of the greatest accomplishments of my life.

###

By Shannon Weirsbitzky

As authors, we write about the things we need to heal in ourselves. I’ve heard that said before and I’ve grown to believe it. As writers we’re often drawn to subjects that have impacted us personally in some way. For me, those moments of truth have been woven into works of fiction.

The funny thing is, I’m not sure we always realize we are in need of healing. At least that was my case when I decided to write a story that had a character with Alzheimer’s. My own grandfather had died with the disease not long after I became a mother. By then, he had forgotten everyone he ever loved, including me. I thought it would be valuable to convey, in a novel for middle-graders, what it actually feels like to be forgotten. Alzheimer’s is a disease that affects so many, and the reality is that few children’s novels were tackling the topic.

The fact that I’d dealt with the disease personally was a plus from a writing perspective. I could tap into my own experiences and pull that emotion into my story. But there were more emotions that came to the surface once I put my fingers to the keyboard. Certainly I relived the loss, but I also found there was still confusion (why it happens and how) as well as guilt (maybe I could have done more).

I’ve heard from both young readers and adult readers, and what they tell me is the same. That even years after the disease has hit them in some way, they are still healing. Readers have shared that the actions Delia takes has inspired them. One woman made her own “memory wall” in a loved ones hospital room where it is beloved by family and staff alike. How wonderful is that! And children ask why Old Red had to die. Why couldn’t he have kept living? Of course Alzheimer’s doesn’t work that way. It takes everyone in its path.

Which is why I talk about the disease. I want kids (and adults) to know that it is okay to talk about Alzheimer’s. There should be no shame in forgetting, or in being forgotten. Together we can cope. Together we can heal.

###

Somebody Stole My Iron: A Family Memoir of Dementia

By Vicki Tapia

My parents, *Trudy and Harry Anderson, had lived a long and fruitful life in *Nelson City and both expected to die there. As their decline became more and more worrisome, I begged the two of them to move closer to me for their own safety, but they adamantly refused. One icy winter, a bad fall and broken hip later, they acquiesced, leaving behind a lifetime of both the tangible: house, car, and belongings; and the intangible: the love of all their remaining friends and support of their church family. Tragically, more onerous losses awaited. After Mom’s diagnosis of Alzheim er’s disease and Dad’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s-related dementia, I watched helplessly, as one excruciating memory at a time, the parents I’d always known, slowly disappeared.

er’s disease and Dad’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s-related dementia, I watched helplessly, as one excruciating memory at a time, the parents I’d always known, slowly disappeared.

Guilt, a constant companion, followed me, not only as I struggled to care for my parents, but to also nurture my new marriage; leaving me feeling I’d done justice to neither. Sorting out everything from how my father had lost his eyebrows to why my mother put comet cleanser into her shoes every morning, I sometimes felt I’d also fallen into the rabbit hole of dementia, right along with my parents. When Mom accused me of stealing their money to travel, I struggled to understand her escalating paranoia and learned neither reasoning, crying nor anger did anything to alleviate the situation. Mom “fired” me on several occasions, and I speak honestly when sharing I secretly wished it possible.

As a way to cope, I kept a journal. As time passed, it occurred to me that others traveling the dementia road might be able to benefit from what I’d learned along the way. That’s when my diary morphed into a memoir. And one truth I’ve learned stands out in my mind: how similar our stories are. There’s comfort in that. My goal in writing this memoir is to offer hope: We’re NOT alone.

Readers’ comments have been both positive and affirming. One reader shared she found this memoir “…A wonderfully true and honest account of surviving dementia. The way the stories are written, all ending with lessons learnt, is a real help to people like myself who are struggling to come to terms with the devastating truth that I am losing the man I love to this nightmare disease. Any help on this path is most welcome and this book, even at the end of a tough day, is an easy read.”

* Names changed to protect privacy